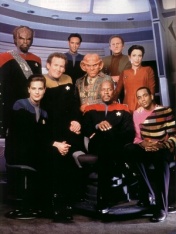

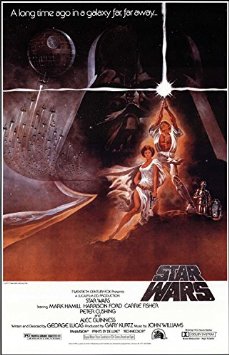

Well, the time has come at last. I’ve said before that there is a trinity of franchises that set the style for popular science fiction today. First, in 1963, there was Doctor Who. In 1966 came Star Trek. And in 1977…

A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away…

Star Wars, now known as Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope, was the brainchild of special effects wizard George Lucas. He made it as an homage to pulp sci-fi of his childhood, and it was a classic revisitation of the Hero’s Journey, arguably the oldest trope in existence.

Of the three great franchises I’ve done the history of, Star Wars is probably the one whose behind-the-scenes history I know the least. That said, I’ve gleaned a certain amount of lore from my parents, who remember seeing them when they first came out.

Star Wars’ saga of the Skywalker family’s quest to master the ways of the mystical Force that permeates the the galaxy and overthrow the evil Galactic Empire and its ruler Palpatine is a perfect illustration of the idea that there’s no such thing as an original story, only fresh versions of old ones. The Hero’s Journey is so basic, and yet in the cladding of Star Wars became one of the biggest deals in pop culture in the last half-century.

If you have infinite time to waste, you can check out the fascinating ‘History of Hollywood‘ series of articles on the TV Tropes wiki. From that, the Star Wars movies were one of the cutting-edge contributors to the concept of the blockbuster film, along with the work of Lucas’ friend Steven Spielberg of the same period. It was a massive hit for all ages (per that wiki, family entertainment had been the exclusive preserve of Disney before then) that seemed to come completely out of nowhere.

Probably the most talked about innovation of the Star Wars movies is in the area of special effects. In space movies prior to this, you moved a model spaceship across a background in a way that made it very obvious that they were subject to Earth gravity and made of plywood – see the old Doctor Who series. Lucas was the first one to keep the model in place and move the camera, resulting in much smoother motion. This innovation was the launching pad for one of Lucas’ many companies, Industrial Light and Magic, still the name in special effects. Only Weta Workshop has, to my knowledge, approached it in prestige since.

Star Wars was and remains a visual feast, from the locations, to the ships, to the aliens, to the action. It runs on raw emotions of exhiliration, awe and suspense. For the more intellectual viewer, it was rife with callbacks to classics like Flash Gordon and echoes of things like samurai legends. Thematically, it’s so universal that people all over the world have gotten into it.

Actually, despite its standing in pop culture and in relation to Doctor Who or Star Trek, there’s an argument to be made that Star Wars isn’t actually science fiction, but like Saga, is fantasy that just happens to take place in outer space. Science fiction is sometimes defined as being about what might happen, but Star Wars is clearly in another galaxy far, far away. That said, the aesthetic, if not the concept, had a big impact on science fiction from that day forward.

The 1977 epic was followed up with the Empire Strikes Back, a significant change in tone that included one of the most famous twists in movie history and, unusually, a situation where the bad guys kind of win.

Return of the Jedi rounded out the trilogy with a resolution of the threads laid in the previous movie and massive all-round epic conclusion that would stand the test of time for twenty years.

It must be said that all of this took a lot out of Lucas, and he defied a lot of convention in doing it, becoming a free agent auteur in the process.

Star Wars was also a pioneer of another, arguably less awesome area: merchandising. Star Wars doesn’t just make money from ticket sales, or video and DVD sales. It spun itself out into a huge market of collectibles like models, toys, posters and so on.

In addition, Star Wars has (or had, at least) something unique in its time: the Expanded Universe. With an entire galaxy to play in, the franchise ballooned into spinoff books and comics, covering the events after Return of the Jedi, before A New Hope, and spaces between, and following the exploits of our heroes and even the most briefly-glimpsed side characters.

This is what set Star Wars apart, I think, from Trek fandom or Whovianism: more than the other two, being a Star Wars fan became a lifestyle unto itself. Star Trek licensed materials were never as cohesive or interconnected, and Star Trek merchandise, in my experience, is harder to find and a lot more downmarket. Doctor Who is moving more in the Star Wars direction since the 2005 reboot, but it has a lot of catching up to do. Besides which, Star Wars, similarly to Warhammer 40K which came after, is a universe so big you can just about live in it full-time, and it’s an ideal breeding ground for Ensemble Darkhorse-type characters like Boba Fett.

It was something only possible because Lucas, having broken away from the Hollywood establishment, had pretty much total oversight of the franchise. In contrast, Gene Roddenberry, for better and worse, was still answerable to a studio. Until the sale to Disney, you could depend on one guy signing off on every little thing.

Which, it must be said, did backfire in numerous ways. Personally, I could never see myself getting into the EU because what little I gleaned always came across as overstuffed. Whether that’s fair or not I don’t know, but what I do know is that after a while Lucas’ creative monopoly started to show its drawbacks.

The most obvious one, and the one even Lucas himself has been known to joke about, is that Star Wars dialogue is as campy as it comes. Everybody gave him hell for that, from Harrison Ford to Sir Alec Guinness, and it’s been a part of the franchise from the word go. Coupled with this is the way he gives characters names that either sound like the babblings of toddlers, or that are hit-you-over-the-head goofy sounding, like the obviously sinister pseudonyms used by Sith or (and this is the one that makes me want to throw something at the screen every time) the portly X-Wing pilot in Episode IV named ‘Porkins.’ The Force Awakens is, for some reason, continuing this tradition in the person of Supreme Leader Snoke.

Before I go on, I should make this clear as it is a point on which I might diverge from a lot of readers. I watch campy franchises like this in spite of their cheesiness, not because of it. I will never understand the logic of watching something to enjoy its flaws. For me, camp is sometimes an historical relic that is acceptable in that context, like the original Star Wars, or something I tolerate because the story is worthwhile anyway, as in the case of something like Tomorrowland. It’s why I never watch things like the Family Guy Star Wars parody (well, that and a general dislike for Seth MacFarlane) or, on the Trek front, Galaxy Quest, because the conversation is going to be them saying, “Hey! Star Wars did something stupid and cheesy!” And me replying, “Yes, I know. Now will you shut up, I’m trying to enjoy it over here!”

Which is why, like a lot of people, my favourite Star Wars movie was Empire Strikes Back, because Lucas merely took general charge of the production and left the dialogue and other fine details up to colleagues. Didn’t improve the Imperial Stormtrooper’s aim much though.

Star Wars was ambitious in having a saga across multiple movies – grabbing us early on by inexplicably calling his first movie “Episode IV” – but it’s clear that Lucas was playing things a little more seat-of-the-trousers than he might have wished us to believe. I particularly remember watching Empire Strikes Back with my Dad as a kid. In one scene Leia kisses Luke – mainly just to tick Han off – and my Dad remarked, “She’s gonna to feel funny about that later.” Leia also discusses in Return of the Jedi what little she remembers of her birth mother, but Padme dies in childbirth in Revenge of the Sith. And there are little early oddities like Vader shouting at Leia in Episode IV, whereas, ever after, his calm stoicism is one of his best assets as a villain.

Another thing Dad pointed out to me over the years is that oftentimes Lucas couldn’t seem to make up his mind who his target audience was. The violence and crises of the movies are pretty mature stuff – I remember being quite shocked as a child by how many of the good guys get shot down in Episode IV. And it was many years before I could get through Return of the Jedi because despite the cute kid-friendly Ewoks this movie also contained the Emperor himself – who I will remind you, looked like this:

Bit much for a seven-year-old to take, really.

Which brings me neatly to the Prequel Triology. I’m probably the oldest generation for whom this was a part of my growing up: the new trilogy of Episodes I, II, and III, beginning in 1999 with the Phantom Menace. This trilogy follows the rise of Anakin Skywalker through the Jedi ranks and his eventually succumbing to the Dark Side and becoming Darth Vader. And, at this point, you will be hard pressed to find anyone over the age of twelve willing to defend it.

Lucas was back in the driver’s seat for this one, as he had been for Return of the Jedi, and unfortunately, due in part, seemingly, to tribulations in his private life, his worst bad habits seemed to get the best of him.

Now, there are legions of articles, comment threads and videos discussing the shortcomings of the Prequel trilogy. In general, another of Star Wars’ dubious distinctions is being one of the first franchises to exhibit a voracious yet unpleasable fan community. If you can stand his interminable videos and obnoxious voice, then the YouTube critic Confused Matthew probably does as thorough a job as anyone of dissecting them.

Among the most common ones were the sloppy and vague background to the conflict – taxation of trade routes, etc. – making it seem arbitrary and hollow; making one’s Jedi potential based more on a blood test than on the content of your character; a plot that barrels ahead leaving hole after hole in its wake; a lot of prophecy and Chosen One talk in a franchise that has never used it; accusations of racist stereotyping; enemies that flip-flop between being funny and scary and failing at both; and of course the most ham-fisted love story ever seen on screen.

That’s not to say that they had no virtues: Episodes I and II in particular had great action, visuals, music and casting, and the fight at the end of Episode I was a masterpiece of choreography. But then Anakin took centre stage and it went downhill fast.

Anakin Skywalker is so arrogant and abrasive you’d think he’d already fallen to the Dark Side! His come-ons to Padme in Attack of the Clones were my younger self’s master class in how never to treat a woman, and he regarded the world through what I’ve since dubbed the ‘Anakin Skywalker Serial Killer Glare’ (see also Jace in City of Bones and the teen big brother in Jurassic World). Beyond that, Lucas’ dialogue got worse and worse, and the battle droids and Jar-Jar stood for Star Wars’ inability to keep a consistent tone.

What always gets me about the Prequel Trilogy is that it contains a terrific story about Anakin’s downfall, but that Lucas doesn’t appear to have noticed it. A lot of aspects of the story that exist as plot holes would have worked if strung together differently. I thought, during Attack of the Clones, Anakin was going to be given legitimate reasons to be disillusioned by the Jedi; the fact that the ‘guardians of peace and justice’ do nothing about slavery in Episode I, their callous attitude toward Anakin’s mother in Episode II, the inflexibility of their code, and the implication in Episode II that there were corrupt Jedi masters involved in instigating the Clone Wars, were, I assumed, setting up the Jedi Order as being in decline, and Anakin’s frustration turning him to a side that promised decisive action. The Seperatist movement could have been a group with legitimate grivances that got coopted by evil. Instead, we get this.

Part of the problem is that worldbuilding in Star Wars has always been a little slapdash: the sheer size and openness of the universe also results in it being quite vague. Sometimes this helps imply a larger world, like C-3PO’s brief line in Episode IV about the Spice Mines of Kessel. But sometimes it undermines the story: at no point does anyone explain in the Prequels what a Sith is or what they want revenge for. What the Seperatists want, their ‘demands’ as Count Dooku puts it, are never shown. The specific remit of the Jedi is never clarified. Most frustrating of all, as I said in my article on the Force Awakens, the Force is never given clear rules as to what you should be able to do with it, at what stage of your training, so that characters tend to find new powers and forget old ones when the plot requires it.

George Lucas’ talents lie squarely in high concept, special effects and production oversight. Despite everything above, though, I don’t mean that as damning with faint praise. Lucas is really, really good at those things. Despite what he makes his characters say sometimes, I’ll also credit that his casting is never less than spectacular. His first ‘Special Edition’ of the first trilogy also made the most of new developments – and more money – and for all the subsquent remasters have contained some questionable decisions, you have to respect Lucas for going outside the system and trying new things. Pity more people in Hollywood don’t try that.

Star Wars is flawed – badly flawed – in myriad little ways, but that doesn’t mean it’s a write-off. It still stirs real emotions in its fans, and taps into very basic elements of storytelling that speak to anyone and everyone. It didn’t become the massive phenomenon it is because of hipster-ironic snarking at its expense. The trappings are strikingly original, the action is exhilirating, and it will be a dark time for the Rebel Alliance indeed when composer John Williams is no longer around to write the stunning scores for these movies. When the hamminess does work, it really works, too – there’s just something about the phrase “you are in command now, Admiral Piett!” The Force Awakens is showing some signs of upping Star Wars’ game in the diversity department – in which it was already fairly strong – and shaking off a bit of the camp, while still retaining its Rule of Cool ethos. As enthralling as Star Trek, as timeless as the Lord of the Rings, and almost as quotable as the Princess Bride, it well deserves its place as one of the cornerstones of geek culture.

May the Force be with you.