I wasn’t kidding when I said that I’ve been a Trekkie for about as long as I’ve been able to walk. My parents are both fans, and I was born the year Star Trek: the Next Generation started. And like a lot of people in the 1980s I was very keen on the movies.

The Original Star Trek took a while to gather momentum into the phenomenon it is today, so it wasn’t until 1979 that Captain Kirk et al returned to prominence by way of movies. Altogether they appeared in six of them, but the ones that most people remember, and the ones that I grew up with, were the informal trilogy of II, III, and IV, entitled the Wrath of Khan, the Search for Spock, and the Voyage Home, respectively.

Everyone knows by now that Wrath of Khan was the movie that Into Darkness was ripping off. It was a stab at a comeback after Star Trek: the Motion Picture flopped – critically, and deservedly – and represented the arrival of Nicholas Meyer, a newcomer to Star Trek, as director and writer.

In Wrath of Khan, Kirk is an Admiral, and chafing at the administrative inactivity of the position when it’s in his nature to, as Dr. McCoy puts it, “be out there hopping galaxies.” It becomes that much more poignant when he arrives for an inspection tour on a training cruise for new officers, aboard the Enterprise, under Spock’s command.

At the same time, Chekhov, also late of the Enterprise, is on an expedition searching for a totally lifeless planet as part of a scientific project called Genesis. When he goes to the surface of one to check an ambiguous reading, Chekhov is horrified to realize that he’s wandered right into the clutches of Khan, the genetically engineered warlord, a fugitive by way of cryogenic preservation from war-torn 20th Century Earth, who once tried to seize the Enterprise, only to be defeated and marooned – events which formed the Original Series episode “Space Seed.”

He uses a local parasite to gain control of Chekhov, and then learns of Genesis and where he can find Kirk, to get power and revenge for his exile. It turns out that Genesis is a new system for terraforming dead planets instantly into garden worlds. The problem is that if used on a planet with life already present, it becomes a weapon of mass destruction. Kirk has to race to stop Khan gaining control of Genesis and destroying his ship and crew, taking horrible casualties in the process.

The movie deconstructs Kirk’s traditional devil-may-care style of leadership, showing the cost in character and lives it can carry. And the cost is high. As everybody probably also knows, this is the one where Spock dies. With the weight of decades of their friendship in popular culture, it was enough to make people weep in the theatres.

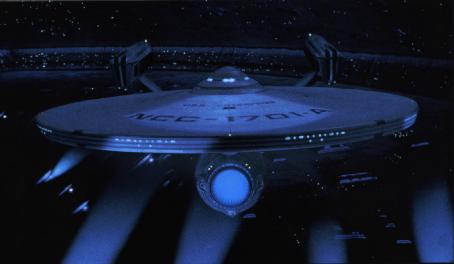

While the situation leading to Khan’s escape is a bit of a stretch (surely lifeless planets can’t be that hard to find), the thematic elements are highly complex and powerful. The writing is excellent, and the special effects the pinnacle of the days (which I sometimes miss) when model photography was the normal method. It brought back all the old cast, including Ricardo Montalban as Khan, and introduced Kirstie Alley to movie audiences as Spock’s protege, Lt. Savvik, who serves as a useful foil for the old crowd.

It’s important to remember that in those days, every Star Trek movie produced was made for its own sake. There was no assumption that sequels would be made. So it was probably a bit out of left field for the gang to be called up for another one: Star Trek III: the Search for Spock.

There’s a funny sort of superstition among Trekkies that odd-numbered Trek movies are never as good as even-numbered ones. And indeed, Star Trek III is a bit silly. I love it, but since this is the specific example of Trek that I started out with, most of it is sentimental.

As the grief-stricken Enterprise limps to Earth, the planet created by the Genesis Device which Khan detonated in a last-ditch attempt to kill Kirk has become a political hot potato for the Federation. Savvik (played by Robin Curtis now) has transferred to a science vessel to explore it.

While Kirk and crew sit idly, after learning the Enterprise is to be scrapped, they are concerned by the illness of Dr. McCoy, who seems to be have been driven round the bend by Spock’s demise. As Spock’s father, Ambassador Sarek explains to Kirk, Spock mind-melded with McCoy before he died, leaving a ‘backup copy’ of himself in McCoy’s mind. Apparently, to free McCoy and lay Spock truly to rest, McCoy and Spock’s body must be brought to Vulcan. Trouble is: they buried Spock on the Genesis Planet, and no one but the science team is allowed there. So, for the sake of their friend, Kirk and his comrades steal the Enterprise and go to Genesis. But they’re in for a shock: the Genesis Effect has somehow resurrected Spock’s body, leaving him a gibbering shell, but with a chance to reunite his consciousness with a living body. It will be hard-fought, because the Klingons have gotten wind of the power of Genesis, and want the planet for themselves.

The whole premise has ‘contrived’ hovering over it. The conjuration of a means to bring Spock back was at least vaguely hinted at in Wrath of Khan; exactly why the Klingons need to go to Genesis is a bit unclear, as is why they needed Spock’s body even before they knew that Genesis would regenerate him. The end of Kirk’s long-lost-son arc from Wrath is kind of cheap. But as with Wrath, the saving grace of the movie is its thematic meaning. For all the hoops they had to jump through, the writers made Search a counterpoint to its predecessor. The phrase that bookends Wrath of Khan is Spock’s remark that “the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.” It summarizes the reasons of Spock’s sacrifice and Kirk’s acceptance of his own responsibilities as a leader. In Search for Spock, though, he counters with “the needs of the one outweigh the needs of the many,” the team’s responsibility to each member. If the basic message of Wrath was ‘one for all,’ then Search’s was ‘all for one.’ The basic moments of friendship, especially Spock’s return and McCoy’s remark to him that “it seems I’ve missed you,” are heartwarming and classic, not something you’d hear in this era of ‘bromance.’ The action sequences are tons of fun too. It also marked a few milestones, including the first extensive showcase of the Klingon language, the first of many appearances of the Klingon Bird of Prey (to this hour, I submit, the coolest spaceship ever imagined), the appearance of a fantastically hammy Klingon played by Christopher “1.21 Gigawatts” Lloyd, and Leonard Nimoy’s directorial debut.

The funny thing about Star Trek III is that it was billed as “the last voyage of the starship Enterprise.” As I said, they didn’t assume they’d be making any more. Mind you, it was technically true: the Enterprise itself didn’t survive the movie.

Star Trek IV: the Voyage Home finds Kirk and crew still on Vulcan, having chosen to return, by way of the Klingon vessel they seized in Search for Spock, to Earth and face the music for their actions. Spock, still not fully recovered from his experience, rejoins them for this last voyage.

But Earth is abruptly cut off when an alien probe of enormous power arrives, sending out a thunderous but incomprehensible transmission that cripples every ship, station or planetary infrastructure around it, and starts vaporizing Earth’s oceans.

Kirk and his anxious crew are stymied, but Spock realizes that the probe might not be trying to talk to humans. He’s right: the transmission is actually in the song of humpback whales. Trouble is, they’re extinct in the 23rd Century. To talk the probe down, they’d need actual whales to understand what it’s saying. With no other option to hand, they decide to risk travelling in time to the 20th Century and get some.

So, yes, this is the one where they save the whales. A lot of people seem to regard that as the biggest joke Star Trek ever played on itself. I don’t understand why. Saving whales is good, isn’t it? And the time-travel technique they use was well-established in the Original Series. Plus, it was a fresh formula after the Enterprise vs. Bad Guy setup of the last two. Regardless, it is true that Star Trek IV is written as more of a comedy. This was customary all through the pre-reboot film canon; Star Trek movies cycle between dramatic and lighthearted every other movie or so.

They arrive in 1980s San Francisco, hide their stealthed Klingon ship in Golden Gate Park, and Kirk and Spock make the acquaintance of the marine biologist who is responsible for the only two humpbacks in captivity. Meanwhile Chekhov and Uhura have to try and jump-start their ship’s engine by breaking into a nuclear reactor (oddly enough the one aboard the aircraft carrier Enterprise) and Scotty, Sulu and McCoy have to get into the good graces of a Plexiglas manufacturer in order to convert their ship into a flying aquarium. Wackiness ensues.

The degree of cultural disconnect between the 20th and 23rd Centuries is the root of a lot of the humour; the fact that our heores don’t use money (“I’ll give you one hundred dollars.” “Is that a lot?”) or Scotty trying to give voice commands to an early Apple MacIntosh (through the mouse, no less) or their tenuous grasp of the colloquial idiom (“Double dumb-ass on you!”). The one everyone (especially J.J. Abrams) remembers is Chekhov asking the way to the ‘nuclear wessels.’ Funny thing is, it isn’t his Russian accent that’s the joke: it’s that he’s a Russian in 1980s America asking the way to the United States nuclear navy.

I have an on-again off-again fondness for farce comedy, so I can see how some people might not have much patience with it. It’s interesting insofar as this movie has a lot more conversational dialogue, rather than the “Captain, sensors are picking up such-and-such” material Trek usually deals in. The coolness of humpback whales is sold quite well by the movie, and indeed, they had the co-discoverer of whale song on the crew: Roger Payne.

Except for a brush with a whaling ship, there’s no villain per se in the movie, but the end, as they struggle to get the whales free and clear to call the probe off is nevertheless very suspenseful. Spock’s ongoing recovery is both plot relevant and rather charming and funny (“Spock, where the hell’s the power you promised me?” “One damn minute, Admiral”). The camaraderie of the crew is strong as ever and it’s all wrapped up with a feel-good ending promising further adventures.

The three movies form a trilogy within the Star Trek film canon, based on Meyer’s and Bennett’s vision of it being very much Horatio Hornblower in space, and Leonard Nimoy’s long-standing acquaintance with the show, its characters and its themes. They were in many respects more grounded than the Original Series or the Motion Picture, and I find them the most aesthetically compelling Trek production prior to Deep Space Nine. James Horner’s soundtracks for II and III are absolutely fantastic (he’s a major reason why the ‘stealing the Enterprise sequence is so exhilarating), and the special effects represent Industrial Light and Magic in their prime. For a lot of people this was the high point of the Original Star Trek cast, if not Star Trek generally. And despite what everyone thinks of Star Trek, and William Shatner particularly, the acting is top game all round.

Happy New Year, and Live Long and Prosper